Hi! Khan here. Thanks for joining me for An Introduction to Narrative Design.

In part one, we covered the discipline as a whole and looked at some of the typical daily tasks of a Narrative Designer. If you missed it, you can catch up here before delving into part two.

Today we will be looking at what a career path into Narrative Design could look like and and how to get started in the field.

It’s a young industry and an even younger discipline, so specifics can vary wildly from project to project.

What does a career path in Narrative Design look like?

Your starting point is likely to be something like:

- Junior Game Designer

- Junior Narrative Designer

- Junior Systems Designer

- QA Tester

- (any number of other entry-level positions)

The mid-point is as a Narrative Designer. As you rise in the ranks, you'll be expected to be able to answer more of the questions outlined in part one, as those answers relate to the game's overall design.

You'll be expected to be able to be decisive, and (like any senior designer) communicate those decisions clearly to the rest of the team as well as to internal stakeholders.

You'll need to be organised about your work, and about the game's narrative -- people will come ask you about this scene or that character, and you'll need to be able to document and keep tabs on a lot of information at once so as to be able to quickly answer them even if you haven't thought about that content in months.

There are also a few potential specialisations within the discipline:

Technical Narrative Designer: the narrative specialist who can code. In addition to some or all of an ND's skillset, they are a maker or tweaker of narrative tools (dialogue editors, branching narrative wranglers, etc) who can script well enough to make the editor do gymnastics it never knew it could.

Mission or Quest Designer: often a hybrid of a level designer and a narrative designer. They focus on the design of, implementation of, and iteration on a game's quests or missions. They will need to be highly proficient in the game editor, and what writing they do will usually be within the context of quests.

And from there we're looking at more senior levels:

Senior (Narrative, Technical, Mission) Designer: the designer with the experience and skills to mentor juniors and lead them by example, to produce high-quality content to a deadline, to work without close supervision, and to interface well with all the other disciplines that often require or request narrative support. Examples of the latter might be to create a clear brief from which a cinematics producer can cast an actor, a flow chart of a campaign's quests used by a systems designer to decide when certain features are unlocked, or a reference-image-heavy bio from which a character artist can concept a new NPC.

Principal Narrative Designer: the master of the ND craft. Their work is hands-on and in the trenches. They must be able to give and take feedback well, to clearly and persuasively explain high-level storytelling principles as well as tiny choices and details to other NDs and to the wider team, and produce high-quality content to a deadline.

Lead Narrative Designer: the person organising and managing a team of NDs; this path is for those who are engaged and challenged by management, leadership, mentorship, and logistics. Like any team Lead, their work will be much less hands-on, though they will still be doing some writing and design. They must champion the game's narrative when high-level decisions are being made, while being flexible and compromising where necessary. They must ensure that the game's narrative work is completed on time and to the required standard, which means exercising their production or project management skills as well as giving useful and timely creative feedback to their team. They must also teach and mentor their team members, encourage and enable their professional development, hire new designers, and in general try and ensure that their team members are challenged, happy, and feel supported.

Narrative Director: the person overseeing the game's narrative vision. They have the deciding vote on narrative decisions, and usually work very closely with the Animation team (in larger or AAA games) to create the cinematic cutscenes. They will also likely manage one or more team Leads, and have the final say in hiring Narrative Designers.

Creative Director: the game equivalent of a film's director. They may have come up through Game Design, Art, Narrative Design, or any number of other paths even from outside the industry. Their job is to hold the project's whole vision in their heads, and therefore be able to make the call on all the little daily decisions that will contribute to its tone and the player's overall experience. If you google what film directors do, you'll see two words come up over and over: "decision" and "choose" -- and that applies to the Creative Director as well.

No matter which path you take, though, the most crucial skill you'll need to master will be people-herding: figuring out what teams, people, or departments aren't coordinating closely enough and will therefore create several components of a narrative feature that won't mesh well; selling your ideas to your team; selling your creative director's new direction to a resentful team whose roadmaps will be affected; getting the right people into meeting rooms together and getting them to hammer out a compromise...

Game Design and Narrative Design are both 1% having an idea, and 90% making people talk to each other.

(The other 9% is having tech issues.)

How do I get hired?

Step one, research. Step two, create your portfolio. Step three, look for opportunities. Step four, network aggressively while you apply for roles.

Step 1: research

You'll need to learn your stuff beforehand as well as learning on the job. Join the International Game Developers Association's special interest groups for Game Design and Game Writing. Read FAQs, and once you have, ask questions. Read recommended books or articles. Watch recommended reviews or videos.

Here's some terms to Google to help get you started:

- Tecfalabs, narrative theories

- David Kuelz, narrative design tips I wish I’d known

- Tomkail.tumblr, irreducible complexity

- YouTube, Extra Credits

- Three act paradigm

- Five act model

- Hero’s journey

- Katie Chironis, getting a job in game or narrative design

- ifdb.tads.org

- emshort.blog, game writing, writing IF, narrative

- voiceoverstudiofinder.com

- gamesindustry.biz, game voice casting

- thevoiceovernetwork.com

- Into the Woods, John Yorke

- The Anatomy of Story, John Truby

- The Game Narrative Toolbox, Heusser & Finley

Start consuming games critically, looking at what stories they tell and how they tell them. Play games outside your favourite genres. Find out what different genres do well or poorly in terms of storytelling. Play on mobile as well as PC and console. Think about what narrative systems or features each platform enables or discourages. Learn how to explain your thought process and opinions. Take notes. Take it seriously.

No-one will pay you to tell stories in games if you can't explain how games tell stories.

Step 2: create your portfolio

If you're applying for any design job, your portfolio had better speak for itself.

I strongly suggest having a master portfolio that contains ALL your best work -- and I do mean your BEST work, not “all your work”. It doesn’t need to be shipped work, by the way. You’ll pull from it to populate the portfolio you actually submit, which will use a modular template into which you can plug-and-play.

Master Portfolio: contains every possible piece

Submission Portfolio Using Modular Template: contains minimum three and maximum six pieces

Here are some types of writing samples your Master Portfolio should include:

- SHORT, concise world-building (setting, lore, character design)

- Character dialogue (cutscene scripts, casting side monologues)

- Combat barks (bonus points if they’re formatted as a recording script)

- In-game text (quest journal, Wanted poster, ad brochure)

- Player-facing non-fiction (tutorials, help text, item shop ads, website

- content)

Your portfolio should also contain design samples, and clear examples of your relevant skillsets. For instance:

- Feature / event / quest designs as well as text

- Pen-and-paper prototypes or LARP / D&D modules

- Links to mods, maps, game jam projects (or play-through vids)

- If a project or design was collaborative, always highlight the parts YOU did

- List and briefly explain any lessons you learned

- Skill ratings with software / tools

- Experience with logistics of getting narrative into games

The most crucial thing about your portfolio?

DON'T MAKE ME WORK HARD TO FIGURE OUT WHAT YOU'RE GOOD AT!

I'm sorry for shouting, but I have been handed 30-page PDFs with no links or organisation too many times.

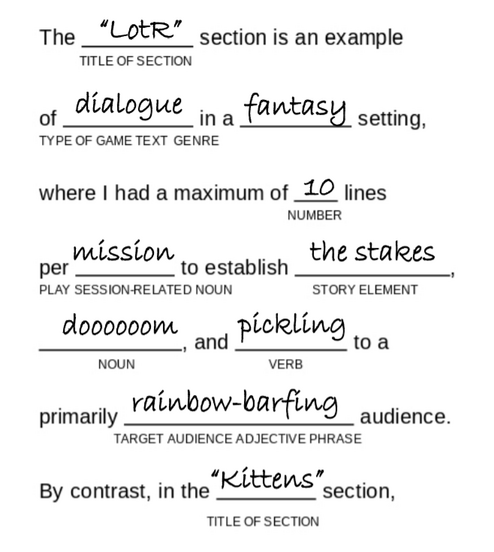

Each piece in your master portfolio should be its own separate section. Each section should be introduced by a list or paragraph explaining what the reader should expect from the piece; for example, “This is the script for dialogue between the PC and a love interest NPC which completes a multi-part quest chain in an Action RPG with a historically inaccurate pirate setting”.

You could also mention what skills it highlights (“This dialogue demonstrates my comfort with humorous writing and characterisation”; “This design document outlines new narrative uses of existing character generation features”).

Include any context necessary to understanding the piece (the key word is necessary: if your friend can follow along just fine without having the game’s setting explained, don’t explain the game’s setting), and a bit of meta commentary if applicable – what surprised you about the implementation of this feature, for example, or what problem this scene was solving, or what problem this design caused and how that was addressed.

You will never submit this master portfolio.

You will instead drag and drop a few of its sections into the clean, streamlined portfolio that you actually submit, one which contains ONLY the work that is most relevant to that particular job (or at least, that type of job). A submitted ND portfolio should contain at least one piece that showcases your game design skills, at least one that showcases your creative game writing skills, and at least one that showcases your technical writing skills -- and preferably no more than six or seven pieces.

Your portfolio will include a table of contents, and ideally each link or heading on it will give me a hint at what I'll find there. ("Title of piece: p.3 / link. A short dialogue.")

I suggest making submitted portfolios into password-protected sections of your website, and submitting only those links and passwords in your application.

Just like your portfolio, you should have a master version of your CV or resume that lists lots of bullet-point detail about every project or position listed.

You will never submit this CV.

You will copy-paste bits of it into the nice, streamlined CV that only includes details chosen for their relevance to the responsibilities or keywords in that particular job's description. If the studio is large, use that job description's wording where possible, in case they use sorting algorithms.

Get a second pair of eyes on your CV and portfolio. Exchange critiques with a friend. Get as much feedback on them as you can. If you’ve not received any invitations to phone screenings or interviews after 6 months or more, it may be worth paying for a portfolio critique from a dev who offers them.

Step 3: look for opportunities

When looking for your first job in Narrative Design, cast a wide net while staying realistic.

The wide net: your first round of searching for your first job in ND should look at not just the exact roles and studios you want, but also at narrative-adjacent roles and roles at minor or less prestigious studios. Some examples of what I mean by “narrative-adjacent”:

• Outsourcing vendor employee (firms who do work for hire for game studios)

• Proofreader or script doctor

• Copywriter for ads, web content, etc

• Project manager for film, print, publishing, etc

• Translator or localisation vendor employee

• Art or animation vendor relations or logistics coordinator

• Recording studio (VO, performance capture, motion capture) employee

If you don’t already have narrative design or game writing experience and are being turned away from ND jobs because of that, gaining some of the above types of experience is the next best thing.

Browser game mills, mobile game studios, III, AAA -- all provide good and relevant experience, because the one thing that most heavily tips the scales when evaluating applicants is their understanding of of the production and life cycle of a game.

Here’s some keywords to search, and remember to search for both design and designer, writing and writer, etc: narrative design (duh), game design (you'll get a LOT of irrelevant results), creative design (you'll get a lot of non-game-industry results), game experience design, game writer, content design (an older term used primarily in the USA), live event design.

Your best results will come from intersections between the above keywords and all the synonyms of: audio, cinematics, voiceover, world-building, character design, cross-discipline.

The realism: competition for junior or entry-level roles is FIERCE. I recently went through over a hundred applicants for a role we advertised for less than three weeks; I'd love to be able to give each one feedback, but finding that kind of time is a big ask. Be patient with yourself as well as with the studios. You're going to apply for a LOT of jobs, and not even hear back regarding many of them; it sucks, but that's the way the system's set up.

More realism: practice evaluating what a job description is actually asking for.

The type of studio will determine a lot about what they’re looking for. Here are two examples:

AAA Studios - makes expensive games with large teams

- Values specialists

- More likely to have a narrative design department

- More likely to demand experience from candidates

- Less likely to provide work-life balance

- Offers less creative control

Game Mill - medium-to-large companies developing casual and/or free-to-play games for mobile, browser, Facebook etc

- Great portfolio-builders

- Value cross-discipline skillsets

- Multiple projects on the go at once

- Often have high churn

- Corporate attitudes & company cultures (not always a bad thing!)

- Will likely have to explain narrative design even more than usual

Day-to-day responsibilities and required software skills are often much more telling than a laundry list of qualifications at the end; the ugly truth is that writing job descriptions is not work that most people do often enough to get good at, so they're often written by someone in HR who is doing their best without intimate knowledge of that discipline's quirks. This can result in cruft: details or phrasing getting carried over from job advert to job advert for years without being re-examined or edited.

It's better to apply to a role for which you're over-qualified and stand out than to be immediately dismissed from a pile of applicants for being vastly under-qualified. That said! The problem with the laundry lists I mentioned is that they often conflate "must haves" with "nice to haves". If you have at least some of the software skills listed, or experience with part of a game's production cycle but not the whole thing, or experience doing most of the things they want but with a different editor than the one listed -- apply.

Cover letters

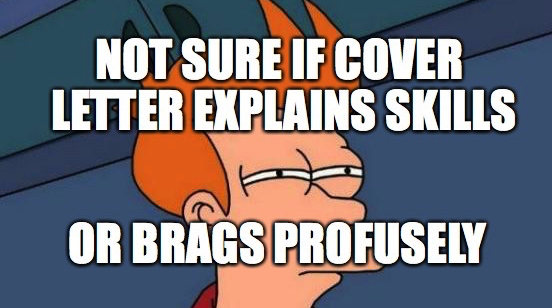

Before we move on, a note on cover letters: In ND, a cover letter is much more important than it is to (for example) UI/UX design, where a portfolio trumps both CV and cover letter every time.

When I read a cover letter, I'm finding out for the first time if you, the applicant, can string a sentence together correctly and communicate a thought clearly.

I'm absolutely going to spot typos and grammatical issues, and they will count against you in a way that they wouldn't or shouldn't in other disciplines.

I’m looking for evidence that you can edit yourself: in other words, your cover letter should be a half-page or so long, or a page at most. Long and rambling sentences, over-explained ideas, and chronic cases of Thesaurusitis indicate a lack of revision.

I'm looking for experience or technical abilities that set you apart. If you've called yourself proficient in a couple of different editors in your CV, pick the one you are best with and call it out if possible in your cover letter ("my favourite project was a Genre!Setting, made in UE4, because it taught me that I didn't have the knack of systems design and because its dialogue made everyone laugh").

Tone-wise, in a junior applicant's cover letter I'm looking for evidence that they know that they still have a lot to learn, and are looking forward to learning and growing as a designer! Entry-level applicants sometimes fear displaying ignorance; others have an inflated sense of their own design skills or instincts. Few hiring managers relish the prospect of stomping on someone's dreams, or of having to disillusion an arrogant colleague who can't take feedback well.

In general, avoid jokes or gimmicks: you never know what kind of sense of humour the reader will have.

Regarding the letter's content, evaluate what skills you already have that would apply to narrative design. It's a very cross-functional discipline, so these are the ones to highlight in your cover letter!

Here are some examples:

-

Audio, Music or Sound: prepping recording scripts, voice acting, in-studio recording, sound engineering, directing, vendor contract negotiation, working with composers, actors, recording studios.

-

Art & Animation: character design, world-building, art direction, infographic & presentation creation, outsourcer wrangling, briefs for vendors, providing constructive feedback, working in editor, source control.

-

Theatre & Film: script writing & doctoring, acting, directing, scene and action pacing, shot framing & composition, talent management, fight choreography, set, costume, prop design, vendor contract negotiation.

-

Programming & Coding: dialogue database creation & wrangling, tool optimisation, scripting ALL THE THINGS, editor wrangling, content wrangling in the editor. (Remember that Technical Narrative Design is a fast-growing field!)

-

Quality Assurance: creating & following procedures, getting the right details from the right people, creating clear & concise documentation, understanding project dev phases, being diplomatic to a dev about their pet feature’s problems.

-

Brand, Sales & Marketing: planning out a marketing campaign, creating ad copy, designing pitch decks, delivering persuasive presentations, defining target audiences & personas, promoting content virality, vendor contract negotiation, working with outsourced writers/artists/publishers.

-

Production & Project Management: cat-herding, making people talk to each other, keeping meetings on track, creating roadmaps, budgets, estimates, & scope/cap plans, coordinating multiple teams/disciplines working on a feature, budgeting for and acquiring outsourced work.

-

Game Design & Systems Design: designing/implementing/iterating on/balancing features, creating design documentation, achieving team-wide alignment, creating and delivering pitches and presentations, designing & implementing live events, designing & balancing metagame elements, bug-fixing & troubleshooting.

-

Level Design: using editors and technical software, understanding player paths and level flow, scripting, coordinating work with other disciplines, having or understanding artistic skills, bug-fixing & troubleshooting.

- Game Writing: world-building, script writing, lore creation and documentation, character design, dialogue writing & troubleshooting, UI text creation, prepping recording scripts.

Again, use the job description's wording as much as possible in your cover letter -- you want to leave them certain that you can do what they're asking. Pick out the things you think you'd be especially good at, highlight how your other skills will help you be good at them, and then politely wrap things up.

A final embarrassing technical note: Many studios, DS Dambuster included, are very careful about what kind of bits and bytes cross their digital portal. Attachments are scrubbed thoroughly, and THIS CAN BREAK LINKS! If you are including a link to your portfolio, personal website, LinkedIn profile, Twitter account, anything -- paste the actual link, or enough of it that a browser can complete the rest. Don't, in other words, say "Find me on LinkedIn here!"; you don't have to include all the https://www. faff, but do give us linkedin.com/in/your-name-here.

Step 4: network and apply

First off, learn to network. It's a job skill just as much as being able to write pithy dialogue, so work at it and practice. If you are actively job-searching and not attending at least two networking events (virtual or -- post-COVID -- in meatspace) a month, you're shooting yourself in the foot. There are a lot of how-to guides out there, so I'll just skim over the two most important bits: how to introduce yourself, and how to think about networking.

NETWORKING WITH PROF. MONTOYA

1. Context-appropriate social greeting.

2. Your name.

3. Your connection to the other person.

4. Your expectations for the relationship going forward and/or a call to action.

Here's an example:

1. Hi there!

2. I'm Khan.

3. I'm in Narrative Design at Deep Silver Dambuster. We met at XYZ / I loved your talk about XYZ / I overheard you mention (Thing XYZ that we have in common / Cool Feature XYZ that I can discuss intelligently) just now / I wrote about (Game XYZ upon which you worked -- make sure they actually did work on it, though, and weren't just at the large studio that made it) for my thesis.

4. I have a quick question, if you don't mind / I'd love to hear your thoughts on it; do you think I could email you about that? / Might you have twenty minutes or so in the next week or two for a quick phone or video call?

Be polite. Respect their professional obligations: don't ask for details protected by their NDA, don't demand mentorship while their project is approaching launch. Respect their time and attention; don't try and monopolise them or ask 35 questions in a row, no matter how useful their answers are or how much you admire them. Pay attention to social cues. If they start looking around, looking uncomfortable, or looking bored, make a graceful exit: tell them how nice it was to meet them and that you hope to run into them again sometime, ask for or confirm their contact details if they've agreed that you can contact them, give them your card if you want them to contact you, and then go find a snack or a drink, or introduce yourself to someone else in a different part of the room.

Follow up. If you've just had a good chat, make a note or two on the back of their business card, in a text file on your phone, wherever. Mine often read something like "So-and-so - blonde, glasses - wrote for GameName - ask her about her character arc flowchart via Discord". Make a note if people say they prefer being contacted or not over a particular channel; some people's email inboxes are graveyards, for example.

The most important thing is to realise that networking is about building up a NETWORK (duh, but it needs to be said) of interesting people in your field. It's not about getting something out of someone immediately. You don't put a Niceness Coin into the Person Machine for them to spit out a job offer; you have an interesting chat with them at some event about a feature or game, you keep in touch with them and get to know them over Twitter, email, in person, whatever -- and when a relevant position comes up at their friend's company, they think of you and recommend you or pass on the job link. And it goes both ways! If you see a nice review of their work on an obscure website you frequent, you pass the article along; if you see a job listing at their company that you're not qualified for, you ask them if they want your qualified friend's contact info; in other words, if you can help them and it would be appropriate to do so, you offer.

Secondly, apply!

Pare down your list of prospects and apply to the most relevant ones first, then the long shots you reeeeally want but aren't sure you're qualified for. Pace yourself; craft one or two good job applications per day. In the meantime, network more. No, more than that.

Follow the instructions. If they want a cover letter attached, attach it; if they want it in a text field on their website portal, or in the body of an email, put it there. If they don't ask for one, see if there's a field for "additional info" or "supporting notes" or something like that and put a brief cover note in there.

The hiring process

This varies wildly from studio to studio, depending on what resources are available to them. It may be a single harried Human Resources specialist triaging umpteen applications for every job by hand, or there may be an entire recruitment team with sophisticated software helping them out. In general, however, you can expect a riff on the theme of:

- You submit your application, containing your CV, cover letter, and a link to your portfolio

- A person or team or algorithm sorts through the pile of applications, triaging for keywords, requirements as spelled out in the job description, and any other criteria the hiring manager has requested

- You are determined to be a promising candidate and your application is passed along to the hiring manager

- You are added to their shortlist and asked for your availability for a screening or initial interview -- almost always over the phone or over Zoom, Skype, Discord et al.

- You are given a design test to complete by a deadline

- You are invited to a second, and then maybe even a third or fourth, video call or in-person interview

- You receive a verbal or initial offer, and upon accepting it (after negotiation) you receive the written offer, then a contract to sign.

The Narrative Design test

It is possible that, before or after your first phone screen or interview with a studio, you could receive a design test. Again, there’s a lot of variance from studio to studio; in general, though, for a designer, they shouldn't take more than a week at most (and even that is pushing it; a day or two is more usual).

I once upon a time WILDLY BOMBED a design test, mostly because it turned out that what they call a "Narrative Designer" was what I'd call a "Technical Mission Designer" or something along those lines (summarised by "way, way better at scripting than I am"). It presumed a history of modding their game, or games like it, that I didn't have. It was great experience for me to bomb it, because it taught me that I Do Not Like Green Mods and Ham, Sam-I-Am, and taught me how to better prepare candidates for what a position and the design test for it would involve.

All design tests are worth taking, because they all give you more insight into what ND looks like at various studios.

Some common tasks in Less Terrible Than That design tests might sound like:

- Design a new weapon / enemy / character for Popular Game Mode or Franchise X

- Create a whitebox level for Popular Franchise Y, calling out enemy spawns, loot drops, and player's path through it

- Explain what the best and worst aspects of your favourite character or class in PvP Game Z are, then say how you'd improve them if you could only change or add one thing

- Here are two characters' bios; write X lines of dialogue between them to convey Y information

- Proofread the following passage which appears to have been translated from Russian to English by someone who apparently spoke neither

- Proofread the following passage which appears to be grammatically perfect (hints: take your time, look for homonyms, use copy-editing how-to resources, and don't neglect to check the spacing, fonts, and punctuation!)

- Pitch a new game mode / character / region for This Studio's Most Lucrative Game, focusing on how they / it would fit into the existing lore and tone of the game

- List out all the types of text that might go into developing Game X

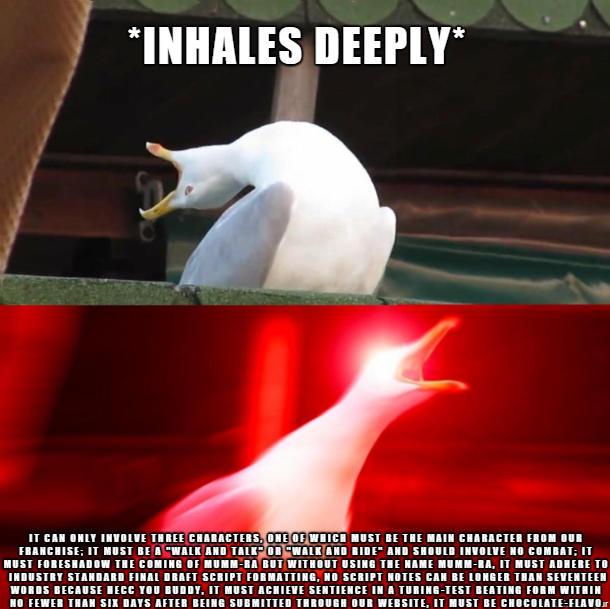

- Write the script for an x-minute-long cutscene, keeping the following restrictions in mind:

Honestly, if you've done your research -- if you've thought about games critically, if you've analysed their narrative elements and are able to discuss those, if you've tried to fill the gaps in your experience through making or modding games on your own time -- you'll do just fine on a design test or in an interview.

A few ND interview questions you might come across:

- What games do you play?

- How do you deal with designing for or writing about topics in which you're not an expert, or for genres you don't play?

- What kind of writing do you do most often?

- How would you go about doing research for a new piece of content?

- How do you estimate how much time a task will take?

- What do you think makes for good character writing? Text prop writing? Game writing in general?

Come prepared with questions of your own, and make sure you thoroughly researched the studio and the types of games they make. It's more impressive and useful to understand their current project's competitors and target audience than it is to frantically try to get 20 hours in on their flagship title before your interview.

Good grief, that was a lot of rambling.

Yes, I know. I should probably learn to edit myself.

For now I'll slink out gracefully; if you have any questions or comments, make sure to leave them on this page or seek me out on Twitter at @Ethnicmutt.

Cheers! Khan